Kids Hacking Space-Time & Quantum Mechanics

Joe wandered between the tables, hands in his pockets, shoes shuffling softly against the linoleum floor. Around him the kids were busy, huddled over iPads, nudging paper cutouts into position. There was the constant background music of snipping scissors and masking tape loops tacking down props. The room buzzed with a kind of chaotic focus.

He stopped mid-step and leaned his hip against one desk. For a long second he said nothing, just looked at them working, his eyes narrowing as though he were deciding something. Then he nodded slightly, as if giving himself permission.

“You know,” he said, voice softer than usual, “I don’t usually tell this story until you’ve been animating for a while.”

The kids froze, sensing the shift.

“But I think you’re ready,” Joe went on.

He took a deep breath, folding his arms. “Heads up, everyone. Lend me your ears. What you’re doing here—this storytelling with sound and motion—you can’t really understand it by me just lecturing, can you? You’ve got to feel it. Let’s pause and reflect on the power of what you’re doing.”

Now the paper characters hung in midair, the scissors stilled, the room at full attention.

“When I was nine years old,” Joe said slowly, “I saw The Jungle Book. Disney’s hand-animated version. And it didn’t just become my favorite movie of childhood. It became the most powerful movie experience of my life.”

His eyes drifted past the classroom ceiling, seeing something far away.

“For three nights afterward,” he said, “I dreamed myself inside that movie. Not just watching it—I was Mowgli. I was there. I sang and danced with Baloo the bear. With the Louis, the king of the swingers, and all characters. I floated down the river, lying on Baloo's belly like a raft. I stared into Shere Khan’s yellow eyes. I met the girl from the village.”

The class was rapt.

“And each night, when I fell asleep, my dream picked up exactly where the last one had left off, and then paused until the next night. I mean—I was there! Baloo was waiting for me when I fell asleep!”

Then suddenly his eyes twinkled.

He puffed his belly out until it bulged like Baloo’s, and began to sway side to side in an exaggerated waddle. His voice dropped into a half-growl, half-croon:

🎵 “Look for the bear necessities, the simple bare necessities…” 🎵

The kids immediately started giggling.

🎵 “The… um… the simple… bear… what is it—forget about your worries and your—something, something strife…” 🎵

Joe stomped a foot, swung his arms like Baloo slapping his belly, and bellowed, 🎵 “With just the bear—neces…si…ties of liiife!” 🎵 He let his voice crack on “life” for comic effect and twirled in a ridiculous little jig, nearly losing his balance.

The kids howled. A few joined in, trying to mimic Baloo’s bumbling sway.

Joe threw up his hands in mock defeat. “See? I don’t even remember all the words. But I remember the feeling. The joy. That’s what got into my nine-year-old brain. First night, Baloo and I danced and sang, then floated down the river. Night two, same river, only farther along, Baloo snoring, my toes dragging in the water, then off to other adventures swinging through the ruins with Louis the orangutan. Night three, chased by Shere Khan the tiger and then into the village, meeting the girl.”

He paused, frozen in his pose. “Then night four—nothing. It was over. I was so sad. For a week I went to bed every night trying to induce that magical experience. But it was gone.”

He swallowed, the memory tugging at his throat. “That has never happened to me before or since. A dream that spanned 3 nights. Only with that story. That animation. Only at that age. But it changed me. Now I have four boys and they’ve all heard me sing ‘bare necessities’ as their bedtime lullaby theme song as they grew up.”

He let the silence stretch. The kids didn’t move.

“When I grew up,” Joe continued, “I met someone who’d worked with the animators who did The Jungle Book. They’re all gone now. But this mentor talked to them and took notes—fifteen notebooks full of their animation secrets. He let me study these notebooks. He showed me how animation actually works. I was blown away. The mechanics. The math. The precision needed to make drawings move. The frames-per-second and tiny spacing changes that mean the difference between slow and fast, believable and silly. All this technical stuff you are learning.

"And —” he spread his hands— “out of all that calculation came a living story so powerful it reached into my nine-year-old dreams for three nights. And then affected my behavior for the rest of my life. Think about that.”

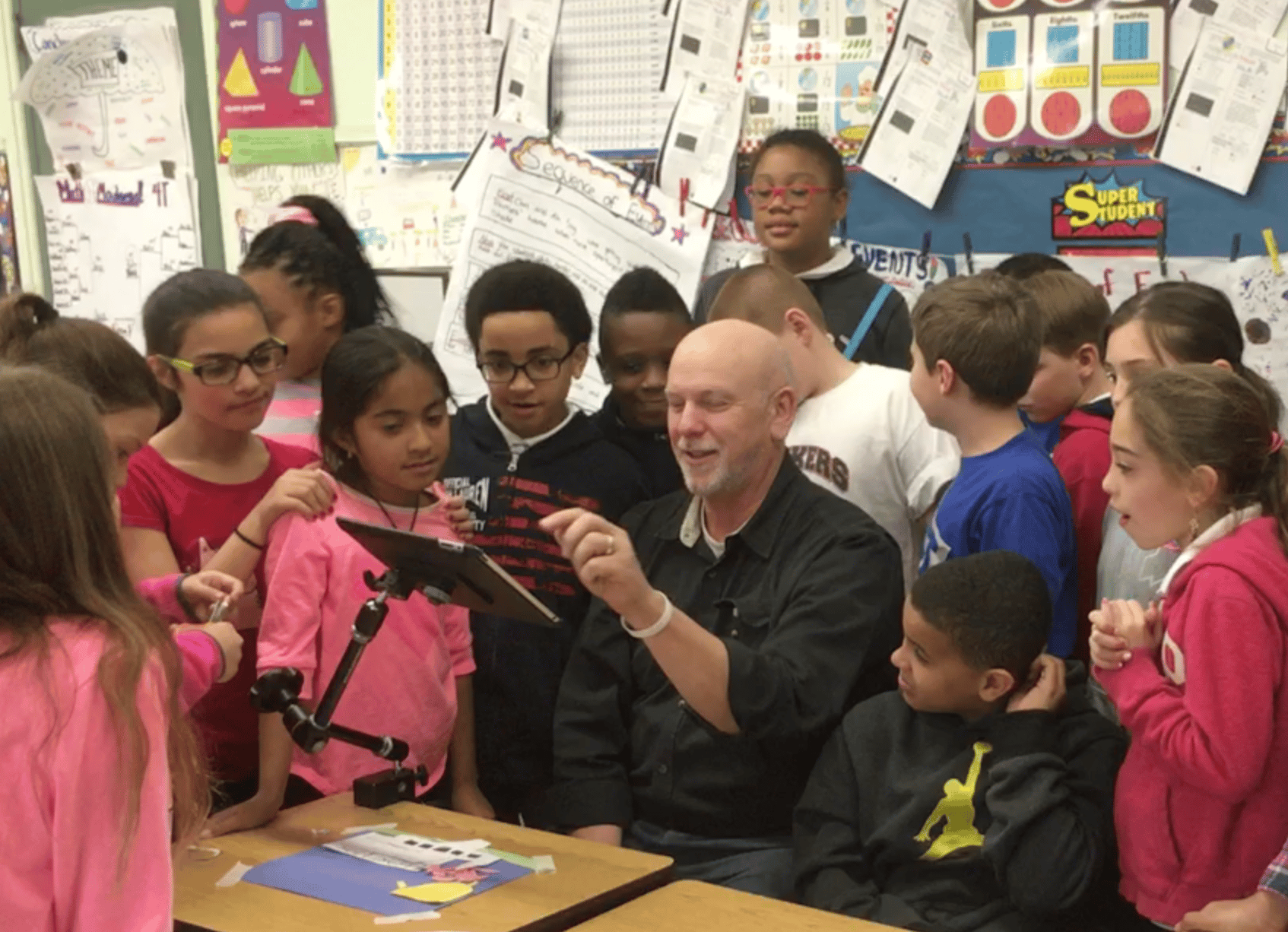

He bent slightly, catching his breath. “I've done a lot of creative jobs in my life, but by far my favorite has been reimagining and migrating almost all of those rules into your classroom and others. These sessions have a direct line to the Jungle Book. And the basics are all here in Animating Kids. It’s all there. Those ancient animators’ knowledge has trickled down directly into this classroom, only you have something they didn't. A computer or phone or iPad with cameras and the internet to share your animations with the world. If those old Jungle Book animators were here today and could see what you have at your fingertips, they’d be very jealous!”

He looked around the room. “But here’s the thing: the magic only works because these animators respected the rules. If Baloo’s mouth hadn’t matched the song, if Mowgli danced too slow or Shere Khan crept too fast, the dream would’ve collapsed. These glitches would have come on stronger then the story. The mechanics matter—but only because they served the story.”

He looked around, eyes serious now. “That’s what I want you to grasp. These rules we are learning—timing, spacing, and sound—they help you get the mechanics out of the way so your audience can live in your story. That’s why we built Animating Kids the way we did. To give you the secret recipes—blinks in three frames, walks in fifteen, spacing small for slow motion, wide for speed. The basics. That’s where you have empathy for your audience. You want them to not see the mechanics. You want them to see, to feel, your story.”

"Speaking of mechanics." Joe straightened up, then walked to the counter and lifted a battered black cylinder.

“You know what this is?” he asked.

A girl squinted. “A… drum?”

Joe smiled. “Close. It’s a zoetrope. One of the earliest animation machines, if not THE earliest. Before movies. Before electricity.”

He held it up so they could see. “This was invented in the 1830s by a man named William George Horner. He called it a ‘daedaleum.’ Fancy name. Later, people renamed it ‘zoetrope,’ which means ‘wheel of life.’ And that’s exactly what it did. For the first time in human history, people saw drawings move. Imagine that.”

He paused. “For thousands of years, humans drew pictures—cave paintings with motion lines, runners on vases, carvings of walking figures on temple pillars. But they were always still. Then, one day, people looked into this spinning drum, and suddenly… boom! Motion. A horse running. A man skipping rope. A bird flapping. The first time anyone ever saw a series of still drawings come alive.”

He slid a strip of paper into the zoetrope. Fifteen sketches of a running man circled the inside.

“Lights, please.”

Someone flicked off the switch. The room dimmed, one overhead beam pooling light down into the zoetrope. Joe spun the drum.

“First, look from the top.”

The kids peered down. The images blurred, fuzzy blobs of running figures whipping around inside the cylinder.

“Now lower your eyes and look through the slits.”

Gasps. A chorus of wows. “He’s running!” one boy shouted.

Joe grinned. “Exactly. That blur of sketches became a runner the moment you saw it in bursts—tiny packets of light through those slits in the spinning cylinder. Your brain smears the images when they whirl by all at once, but create short flashes, strobes, and you eyes tell your brain to stitch them together into motion.”

A girl tilted her head. “How?”

Joe raised an eyebrow. “Great question. Scientists call it persistence of vision. That’s why you still see a sparkler’s trail in the air, even after it’s gone. Or why you can wave your hand fast and it looks like there are six of them.”

Joe points out the window. Stare out there at that tree for about five seconds." The class turns and collectively looks outside the window at a lone tree.

"Now, close your eyes and tell me what you see!" Joe challenges.

"A ghost of the window!" yells one kid. "For about three seconds! and then it disappears“.

Joe interjects, "That is persistance of vision. Even when you close your eyes, what you look at "persists" for a bit. In the Zeotrope, those slits "blink" your eyes while your brain is holding on to the old picture while the new one arrives. If those bursts come just right, the brain blends them into motion." Joe says.

He tapped the zoetrope. “That’s a "quanta" or "packet" of light. One burst, one frame, one moment. Then another. Then another. Your brain does the rest. But the grand secret is that for your to see invented motion on a screen, it needs to be chopped into little bursts of light.”

The kids were spellbound.

“And here’s the kicker,” Joe said. “That’s still how it works today. Every movie, every video game, every TikTok clip, every ESPN highlight—frame after frame, packet after packet. Your whole screenager lives are run on frames-per-second. Nothing’s changed since 1834. It’s all just better disguised.”

A boy frowned. “So if I look down the top again…”

Joe spun the Zoetrope again. The boy peered in, shook his head. “Still just a blur.”

"Aren't the mind and the eyes connected in mysterious ways?" Joe asks.

A lot of nods.

"Fifteen frames a second is what we’re working at. Twenty-four frames is what they usually use in the movies. Thirty for TV. Sixty and up for games. It’s all just tricking your brain with the right rhythm of light packets. Honestly? All of this—the timing, the spacing, the rhythm—is the same territory Einstein and the quantum physicists went exploring later. You’re not studying equations yet, but you’re playing with the same mysteries of space and time and light.”

He clapped once. “Funky, right?”

The kids nodded eagerly.

“Alright then,” Joe said, “let’s talk spacing and time. Turtle Group—your mama turtle scene?”

Groans erupted.

Joe held up the Turtle Group’s iPad and hit play on scene three.

“Right now, mama turtle’s moving at freeway speed. She’s supposed to be slow, worried, looking around for Junior, remember?”

He beckoned. “Up front. I need volunteers. I need a turtle, a director, and a timer.”

Hands shot up. Shaniqua became the timer, Daquan the director, Juan the turtle.

“Juan is going to get down on his hands and knees and act out this scene for real. He is going to look worried, walk slowly like a turtle, and call out for her baby. You got it Juan?”

Juan immediately dropped to his hands and knees, already wobbling his worried head dramatically to spontaneous laughs.

“Shaniqua, start tracking the seconds on the clock when Daquan gives you the cue! Juan, you start walking when the director says…”

Joe turned to Daquan. “What do directors say?”

Daquan grinned, puffed his chest, and shouted, “Lights! Camera! Action!”

Juan crawled across the floor slowly, dragging his knees, wobbling, calling in a grandmotherly falsetto, “Junior! Juuuunior! Where are you, dear?”

The class erupted.

“Cut!” Daquan yelled, and Juan hopped up off the floor, brushing dust off his jeans while he bowed to immediate applause.

“How long?” Joe asked.

Shaniqua checked the clock. “Eight seconds!”

Joe beamed. “Eight seconds. At fifteen frames per second, how many frames is that?”

A chorus of muttering. Fingers counted. Finally, two kids shouted together: “One hundred twenty!”

“Exactly,” Joe said. He tapped the iPad where the turtle animation lived. “But you only shot fifteen on your first attempt. That’s why she looks like a race car."

Groans. “Do we have to reshoot it? 120 pictures will take foreeeeevvveer.”

“Welcome to Hollywood,” Joe said cheerfully. “Reshoots happen.”

The kids laughed and groaned at the same time.

“Alright,” Joe said, clapping once. “Now here’s what I want everyone to do. Go back to your projects. Find the scene that looks weird—too fast, too slow, too choppy. Every one of you has one. You know the one I mean. The one that bugs you when you watch it back.”

The room filled with nervous laughter.

“I want you to act it out. Pick a director, a timer, and an actor. One of you is the character, one is keeping time, one is calling the shots. Perform your scene in real life. See how long it really takes. Then do the math: fifteen frames per second. How many pictures will you need to get it right?”

A buzz swept the room as kids returned to their clusters. Chairs scraped. Stopwatches appeared on phones. Paper cutouts were set aside while students stood in to play their characters.

From one corner, a director shouted, “Lights! Camera! Action!” and a girl pretended to sneak across the floor, as if she were going to steal a rocket. Her partner timed her while the third kid called out, “You’re walking too fast! Slow down!”

Across the room, a kid was mock-bowling in exaggerated sliding steps. “Wait, wait!” their timer yelled. “That was only two seconds. At fifteen frames per second, that’s thirty pictures! No wonder it looks like he’s teleporting!”

Laughter erupted.

Joe moved from group to group, listening, correcting, encouraging.

“Good, good. Count it out. How many frames for that door to creak open? Five seconds? That’s seventy-five pictures. Worth it? Maybe. Maybe not. You decide.”

Near the back, two boys argued.

“It’s fast!” one insisted.

“No, it’s slow!” the other shot back.

Joe leaned in. “Settle it with a stopwatch. That’s what the pros do. Hollywood directors don’t guess. They test.”

The room became a patchwork of little film sets, each one alive with commotion. Their new appreciation for the mechanics of motion ruled.

Students crawled on the floor, staggered dramatically, waved their arms in slow arcs, all while timers shouted seconds and directors barked “Cut!” Laughter rolled like waves across the room.

Joe stood in the middle, turning slowly, taking it in. His heart swelled. This wasn’t kids fiddling with paper anymore. This was kids learning the grammar of motion—the rhythm of time itself.

He raised his voice over the noise. “See what’s happening? You’re discovering it for yourselves. Timing and spacing aren’t abstract rules—they’re real. You can feel them. Fast, slow, jerky, smooth—it’s all about the math, the rhythm, the packets of light your audience’s eyes can handle.”

The kids quieted enough to listen.

“Frames per second matter. It’s all about rhythm. Give the brain the right rhythm, the right sequence and number of "light bursts" and it believes. Break the rhythm, and it doesn’t.”

He clapped his hands. “Funky, right?”

“Yes!” the kids chorused.

Joe says, lowering his voice again, “When you set your timing right, your audience stops noticing the mechanics. They stop seeing cutouts. They start seeing turtles searching for their children. Or bowling balls sad to be gutter balls. Or bears dancing in the jungle.”

He puffed his stomach out again, swayed side to side, and bellowed:

🎵 “The bear—necessities… the simple… uh… bare… something-ities…” 🎵

The class started stomping and clapping along, doing their best-big-belly-bear impersonations.

Joe bent over, laughing at himself, then wiped his forehead. “See? Even when I butcher the words, the rhythm carries it. That’s what you’re after. Rhythm. Timing. Spacing. Get those right, and the story sings.”

He looked around at the flushed, laughing faces, the kids still buzzing with stopwatch energy.

“Do you realize how powerful that is?” he asked quietly. “In this room, you are bending space and time like Einstein! You’re controlling the physics, the quantum mechanics of the universe you've created. And your audience—strangers—will believe you. That’s a superpower.”

A hush fell.

“You are pulling the knobs and dials like the Wizard of OZ behind the curtain. These are the secrets. And they are not exotic. Just respect the timing, do the math, shoot frame-by-frame, second-by-second, you’re making stories that will land in people’s heads. Maybe even their dreams.”

He looked around. “I think you get it" He paused. “That’s the marriage right there. The wonder and the math. The mystery and the mechanics. The dream and the stopwatch. That’s the art of animated storytelling.”

Then, with a final grin, Joe puffed out his stomach one last time, shuffled like Baloo, and belted—off-key, half-forgetting the words, but full of joy:

🎵 “Look for the bear—necessities… forget about your worries and your strife…” 🎵

The kids roared, clapped, stomped, some shouting nonsense lyrics along with him.

Joe bowed low, laughing at himself, then straightened. “Alright. Back to work. Lights. Camera. Action. Let’s see some stories worth dreaming about.”

Joe Summerhays is the creative force behind Animating Kids and Animation Chefs, the globally adopted anti-slop media literacy platforms that turn learning spaces into movie studios and students into visual storytellers.

AI can generate infinite content. Joe teaches kids to generate meaning. They learn how sound and motion persuade, shape emotion, and steer perception, then use those tools to author stories on purpose.

Over the past two decades, Joe has trained 25,000+ kids and educators across 20+ countries, giving schools a practical, repeatable system for real media agency.

An award-winning creative executive across software, TV, publishing, and advertising, Joe brings industry-grade persuasion into primary education and flips it into kid defense. His Animation Chefs Colored Hat Levels, inspired by karate belts, guides media coaches from storytelling basics to full film production.

Using handmade cut-paper stop motion, Animating Kids keeps it human. It slows media down frame by frame so students can see how it works, then rebuild it into stories they own. The result: kids who spot manipulation, resist AI slop, and communicate with clarity.

More Testimonials:

"I am impressed by...these programs, providing young people with the skills to become creative and critical thinkers...this shares my dedication to nurturing the next generation of filmmakers and visual storytellers."— Steven Spielberg - Referencing the work of Joe Summerhays“

"Joe (Animating Kids Founder) has turned the art of movie making for kids into a science.” — Jonathan Demme - Academy Award-Winning Director

“I absolutely love Animating Kids...you have no idea how amazing it is for a span of K-9. I’ve got the whole building covered and my planning was done for me. The kids LOVE the Animation Chefs. Win, win!!”— J. Tuttle - Media Specialist

"When I found Animating Kids it changed everything. Small and not so small humans became masters of sound and motion on any subject via small group PBL dynamics."— Rachel - Tech Coach - Quebec

“Animating Kids has changed everything! Fun, relevant media-making lessons for kids, and total P.D. for my non-film making teachers. A complete solution!!” — Principal - Bronx NY

"Animating Kids really helps focus our students during remote sessions…it keeps them so engaged. Your secret recipes are a life saver." — Marisol - Sacramento Ca

"The kids love the demonstrations and it is P.D. for me as I tee it all up. Animating Kids makes me the coolest educator in their lives!" — Charlotte - London UK

"This is the most important skills-based content for today’s kids. I don't think primary educators get how impactful this approach can be. It respects media content creation as the basic literacy it is for today’s kids. — Monique - White Plains NY

“We went through the entire process (PD workshop) of learning animated filmmaking with our tablets and smartphones. We could barely keep up. In the end we came away exhilarated rather than exhausted.” — Cathy S. - Librarian“

"My head was spinning. It involved: math, writing, science, team building, art, language arts, engineering, improvisation, innovation, acting, etc. Along with another dozen areas I can’t recall. Sneaky comprehensive. Mind blown. Can’t wait to use it in class.” — Marcia - 4th Grade Teacher

“Animation Chefs have created a really inspired program! My test group of (hardened gang members) like to laugh at the videos, and they love the simple clear explanations. They just have a blast...”

— G. Zucker Austin TX

"Thank you SO much for sharing your wealth of information and opening this world to every kid! I first learned about you when my husband introduced our daughter to you. Now I am bringing it into my after school program. I’m so psyched!" — Joy H. Retail After School Specialist

"Kids sign-up for robotics, coding, and stop motion sessions. After taking all three, they rate stop motion as their favorite track BY FAR. Animating Kids is key to our success." — Shane V. After School District Lead