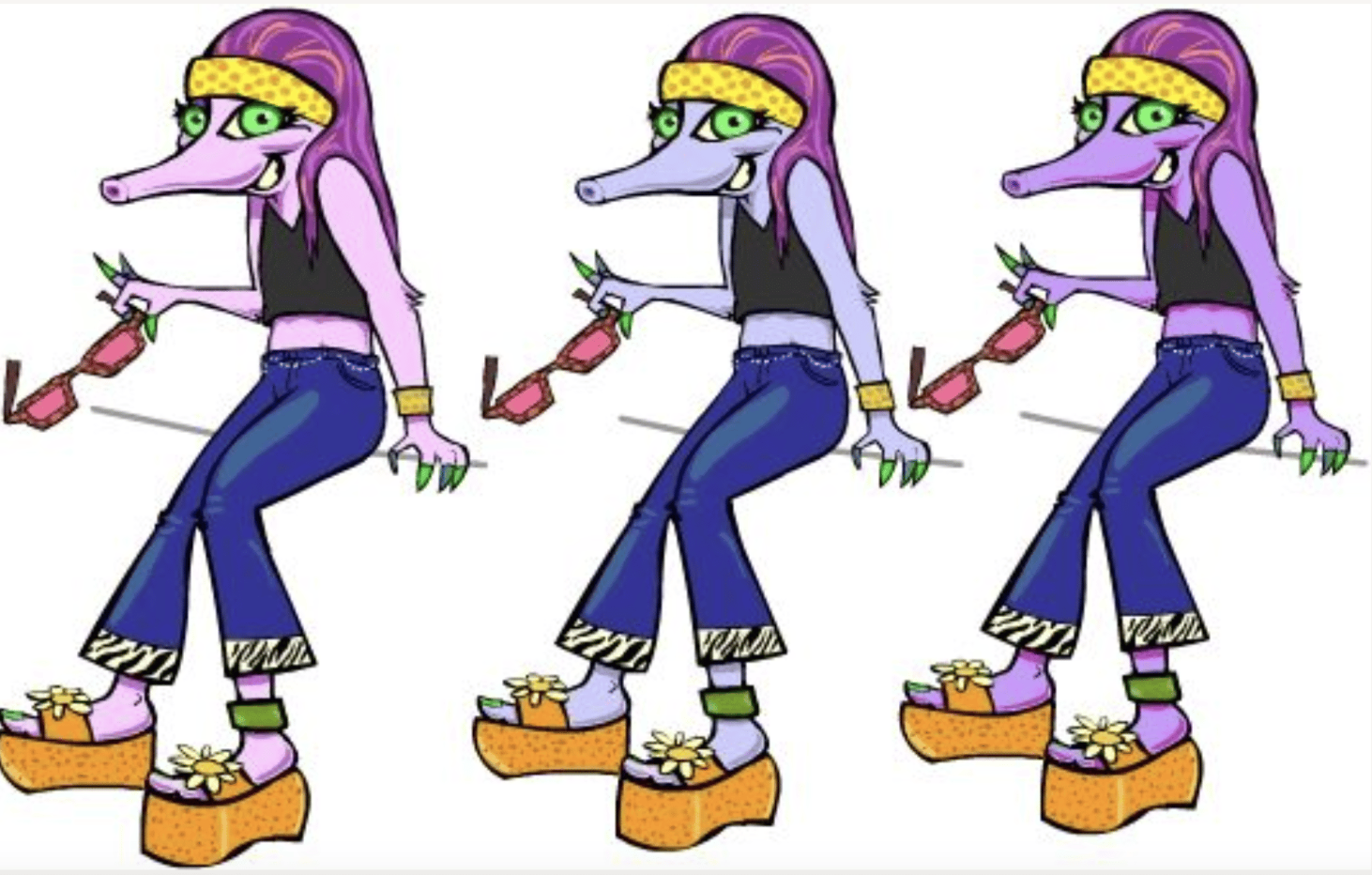

Maggie Mole Sketch - Story Below

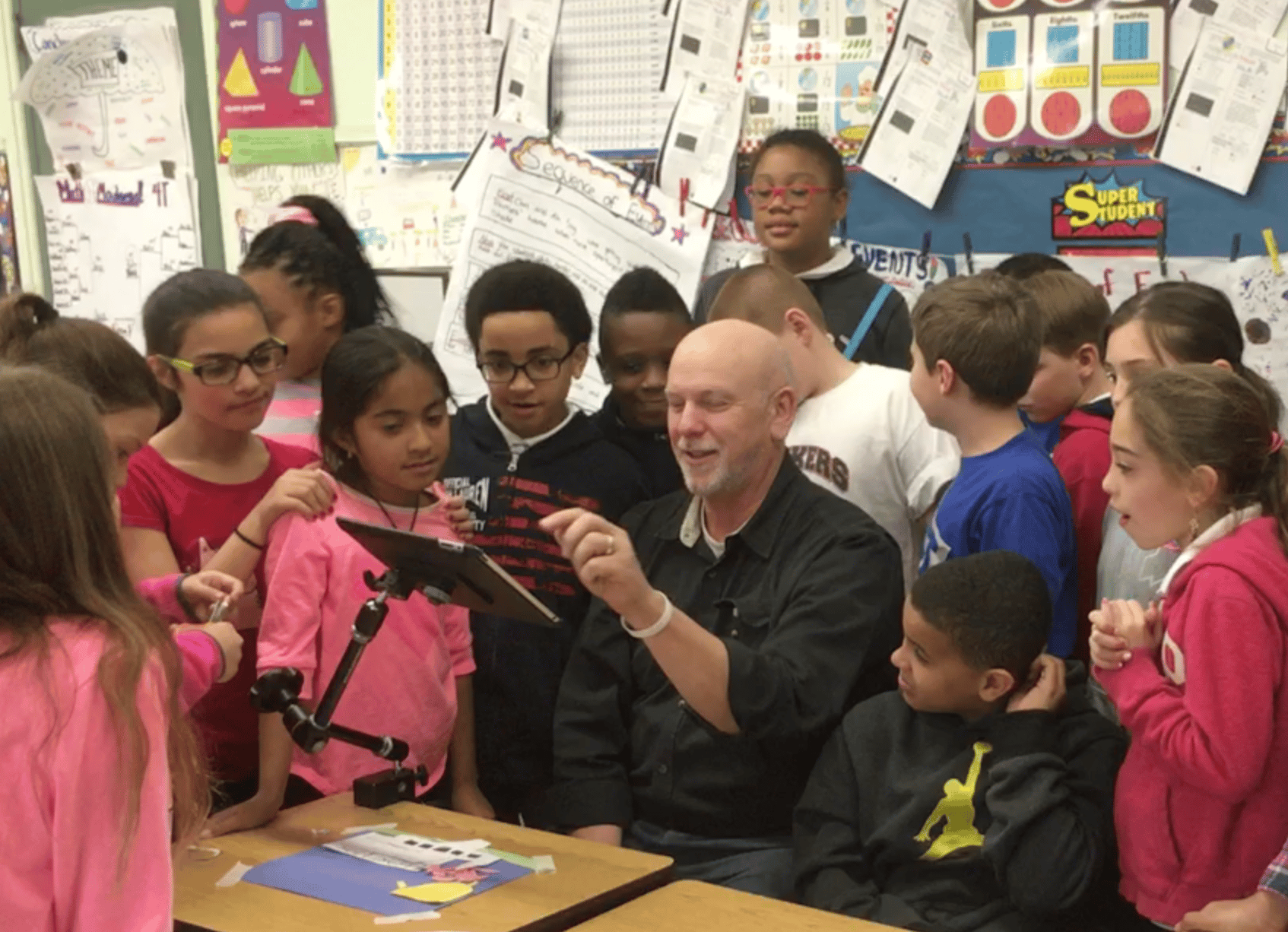

Joe steps into the classroom.

The hum of activity fills the air. Small clusters of students lean together, their iPads glowing faintly as they prepare to shoot their next scenes.

He smiles to himself.

“They haven’t even noticed I’m here,” he thinks. “Perfect. It means the work belongs to them now. They’re not waiting for the teacher or the visiting expert. They’ve claimed it.”

He drifts slowly between tables.

At last, recognition.

“Oh, hey Joe! Did you see our scenes from last week?”

“Not sure,” he says. “Play them for me.”

They scramble to the monitor and tap play.

The bowling ball movie.

Already they’ve modified the story.

The crossed-out storyboard frames are scribbled over with changes, which they had already animated.

“Just like the real world—really messy!” Joe affirms.

“Really messy.”

Joe was so relieved to get back to the kids. “I like this kind of messy”, Joe thinks to himself.

Joe had a messy creative meeting that morning in the city. He was exhausted and these newly minted storytellers added back the breath of life

More on that below.

“You discovered exactly the best way forward in your movie and you couldn’t tell until you were at it for real! Sometimes you don’t knew what you don’t know until it bites you in the …”

The kids laugh!

I’m so proud of you guys having the courage to change things up this late in the game!”

He moves on, greeting each group.

He really isn’t needed. Not in the immediate sense.

The machine is running on its own.

The kids are directors, animators, writers, sound designers and editors. He has become a bystander.

It’s the best kind of irrelevance.

But while his body moves between tables, Joe’s mind keeps slipping back to earlier that morning.

To the other messy room he’d been in that day.

A very different room.

It actually started months ago in a lecture hall at NYU. Joe was workshopping with graduate students, future media architects, demonstrating how attention, sound, motion, UX/UI and story pull together to engage the human nervous system.

The professor introduced him with a note of pride: Newsweek had profiled Joe years earlier as a young media designer. He’d helmed an educational software title that won Newsweek’s Editor’s Choice Award. Old news, but still a signal: this was someone who could see where youth culture and tech were headed before others tuned in.

In his talk, Joe showed examples from his firm’s commissions—Apple, Disney, Olympics work, Times Square animation—projects where entire city blocks became a canvas.

Afterward, a student approached him and mentioned Maggie Mole, a youth TV/Internet project Viacom was struggling to lock down. She was interning on it. Several firms had pitched, but none had captured the character.

Maggie, she said, was aimed at nine-to-twelve-year-olds.

Joe quizzed her.

“A mole?”

“Yes. A mole.”

“Sounds intriguing,” he said, “but I’m pressed for time.”

He grabbed a scrap of paper and dashed off a sketch—bell bottoms, midriff top, oversized sunglasses, a flowered headband—half joke, half instinct.

“There she is.”

He snapped a photo of the sketch and handed it over. (See top of this post.)

“See if they’ll take that as a pitch,” he quipped.

That casual napkin drawing—tossed off in seconds—landed the Maggie contract, thanks to the intern who pitched it in Joe’s absence.

A few weeks later, Joe came straight from the first Maggie meeting to supervise the fourth graders’ animation projects.

The meeting was at 1515 Times Square. Viacom. The old MTV building—once pulsing with youth culture, now repurposed into cubicles and war rooms.

Maggie Mole was green-lit, a bet to capture the nine-to-twelve market.

Maggie Mole—pronounced Mo-Lay—lived underground in a burrow styled like a teenager’s bedroom: string lights, Broadway posters, racks of clothes. She dreamed of stardom. TikTok, YouTube, TV, streaming—whatever would take her.

The hook was clever, in a slightly chilling way. Kids could dress her up, decorate her burrow, interact with her online. Algorithms would track every click. Maggie’s “career” would be driven by audience data—numbers determining whether she “landed” a series, a cameo, an influencer campaign. She was 2D underground, 3D above ground.

Then came the room.

Joe stood before a conference table of media pros, dead serious, debating Maggie’s midriff like it was national policy.

“Does she have abs?” someone asked.

The walls were plastered with images: Britney at twelve. Jessica at twelve. Miley at twelve. Icons across decades—every girl who had “hit” at that age, pinned up like a museum of market precedent.

Joe picked up a marker and sketched Maggie on the whiteboard, riffing on the napkin version.

“Two-pack.” “Four-pack.” “Just a whisper of obliques.” “Absolutely not six-pack.” “Drop the waistline.” “Hip bone, but not too much.”

Belly button placement. Shadows. Contours. The edge of scandal.

The seriousness was absolute.

The intensity absurd.

All of it aimed at one question: how close can we get to “aspirational” without crossing the line?

And beneath the absurdity was something darker.

This wasn’t idle art direction. It was attention science with a smile. Every sketch was a lever meant to pry open insecurity, desire, comparison.

Joe stayed for the decks.

Graphs of attention spans. Charts of demographics and ad spend. Slides mapping the market opportunity like they were planning a lunar landing—except the moon was a nine-to-twelve-year-old’s nervous system.

And there was Joe, caught in the current, drawing in real time, feeling the raw seriousness underneath the weirdness.

Their careers, their investors, their budgets—hinging on whether a cartoon mole’s torso could help sell jeans, lip gloss, shampoo.

He left the meeting an hour later, dusted with dry erase residue and irony.

Many more meetings eventually produced a finished Maggie.

Joe was paid and released.

The final Maggie Mole for HBOFamily. Abs toned down to almost nothing.

Joe startles back into the present.

He comes to and looks at the kids bent over their projects, arguing not about abs but about whether their bowling ball character should laugh before or after hitting the pins.

Their worries are tiny, human, full of joy.

Here, the stakes aren’t brand loyalty or market share.

Here, the stakes are: does my classmate laugh? does my scene work?

The contrast warms him.

This isn’t just a fun animation project.

In Joe’s mind, it’s the front line in these kids’ future.

With four kids of his own, he knows the stakes. The media machine is accelerating—everything migrating into the screens in their pockets, designed to grip and never let go.

And in Times Square that morning, he’s seen the other side of it.

Smart minds, straight faces, deadly serious about keeping kids from clicking away.

“It’s just business, right?” Joe muses.

Wrong.

Who is countering this dynamic?

Who is pulling back the curtain for real twelve-year-olds, showing them the machinery designed to bulldoze their sensibilities?

One frame at a time, one kid at a time, he begins to see his role not just as content coach—but as the one who slips them the antidote before the poison sets in.

He’d be the magician exposing the tricks—the gears, the motives, the hands behind the curtain.

Every trick has to be named: how misdirection works, how color bends emotion, how motion stirs the eyes, how reframing keeps dopamine flowing.

That is the real work.

That is the fight worth showing up for.

And maybe, he thinks, as he holds up each iPad and the day’s new scenes flicker across the screen, this is the work that makes sense.

The boardrooms have their budgets and decks and endless debates over cartoon abs.

But here—here there is laughter, invention, kids surprising themselves with what they can make.

Here confidence in media creation is flourishing.

In future he knows he’ll lean harder into exposing the tricks of the trade, pulling back the curtain more deliberately.

For today, though, he lets it rest.

Smiling at the same joy in these kids that pulled him into media in the first place:

The magic.

The astonishment.

The meaning-making.

Joe Summerhays is the creative force behind Animating Kids and Animation Chefs, the globally adopted anti-slop media literacy platforms that turn learning spaces into movie studios and students into visual storytellers.

AI can generate infinite content. Joe teaches kids to generate meaning. They learn how sound and motion persuade, shape emotion, and steer perception, then use those tools to author stories on purpose.

Over the past two decades, Joe has trained 25,000+ kids and educators across 20+ countries, giving schools a practical, repeatable system for real media agency.

An award-winning creative executive across software, TV, publishing, and advertising, Joe brings industry-grade persuasion into primary education and flips it into kid defense. His Animation Chefs Colored Hat Levels, inspired by karate belts, guides media coaches from storytelling basics to full film production.

Using handmade cut-paper stop motion, Animating Kids keeps it human. It slows media down frame by frame so students can see how it works, then rebuild it into stories they own. The result: kids who spot manipulation, resist AI slop, and communicate with clarity.